John Virtue (Monotypes) British, b. 1947

-

OverviewCentral to Virtue's monotypes is that effectively they are paintings on paper and, as such, are a continuation of his work as a painter.

A monotype is a unique print. The image is created by applying ink to a printing plate, using brushes, rollers, fingers or other means. The image on the plate is then transferred to a sheet of paper using a press. Although a second impression can be taken, such subsequent printings will be different from the first, being lighter in tone or because the plate will have been reworked.JOHN IS AN MA GRADUATE OF THE SLADE SCHOOL OF ART

Now in his seventies, John Virtue is considered one of the most distinguished painters working in the United Kingdom today. His work is included in the collections of TATE, London, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, British Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, Government Art Collection (UK), Arts Council of England and The Courtauld Institute. He is a painter whose work rides a fine line between figuration and abstraction. The artist has always worked in black and white.In 2006, John began experimenting with monotypes for the first time. The following year, he participated in a scheme run by Mike Taylor and Simon Marsh of Paupers Press in cooperation with the International School of Graphics in Venice. During this time, Virtue produced over three hundred and sixty prints of London and Venice. In 2009, following his move to North Norfolk from Italy, he completed a further series of monotypes around Cley-next-the-Sea and Blakeney Point.

Prices for monotypes £1,000 - £3,500In 2019, a monograph covering over forty years of John's work was published by ALBION Ridinghouse. This two-hundred-and-eighty-five-page illustrated book provides a substantial overview of the development of Virtue's art. It traces his close relationship with locations in Devon, Exeter, London, Italy and Norfolk. The critical text is provided by Paul Moorhouse, Ex TATE and previously, Senior Curator, 20th Century Collections, National Portrait Gallery.

The gallery has work from all periods of the artist's oeuvre. If you are thinking of buying or selling, please contact us. -

London Monotypes

-

-

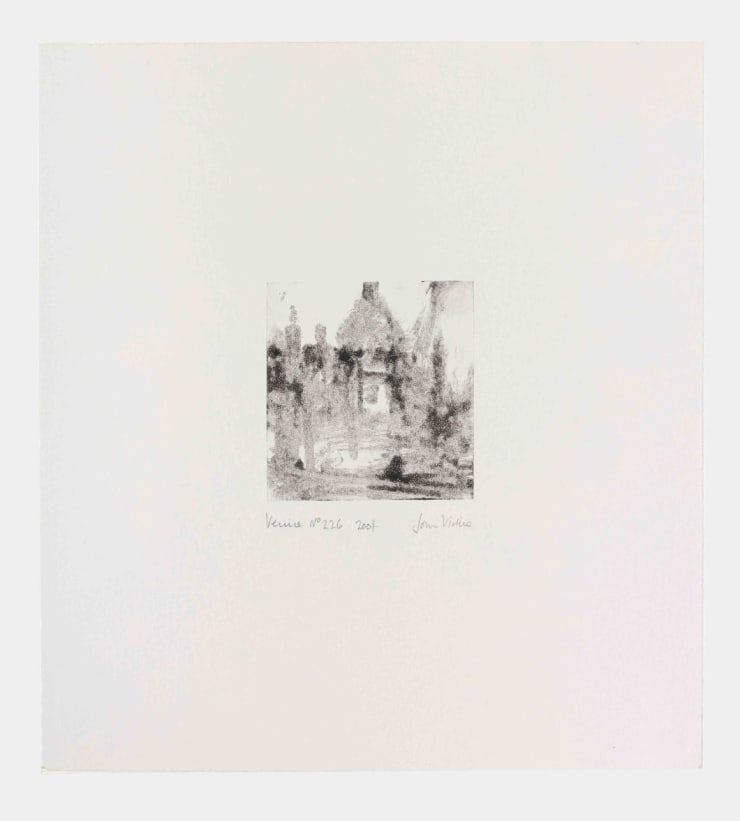

Venice Monotypes

-

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.54, 2007

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.54, 2007 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.80, 2007

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.80, 2007 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.113, 2007

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.113, 2007

-

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.114, 2007

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.114, 2007 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.132, 2007

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.132, 2007 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.148, 2007

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.148, 2007

-

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.178, 2007

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.178, 2007 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.179, 2007

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.179, 2007 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.224, 2007

John Virtue (Monotypes), Venice No.224, 2007

-

-

-

Norfolk Monotypes

-

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.1, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.1, 2009 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.18, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.18, 2009 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.22, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.22, 2009

-

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.23, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.23, 2009 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.28, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.28, 2009 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.31, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.31, 2009

-

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.33, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.33, 2009 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.36, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.36, 2009 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.42, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.42, 2009

-

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.44, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.44, 2009 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.53, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.53, 2009 -

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.54, 2009

John Virtue (Monotypes), Norfolk No.54, 2009

-

-

-

Essay by Paul Moorhouse

Art historian and curator. From 2005-17, Senior Curator of Twentieth-Century Collections and Head of Displays (Victorian to Contemporary) at the National Portrait Gallery, London.First published in 2007 to accompany the 'LONDON VENICE' monotype exhibition at Marlborough Fine Art, London.

These monotypes form a selection from a much larger body of work - more than three hundred and sixty prints - completed by John Virtue in several phases between October 2006 and September 2007. Taking London and Venice as their respective subjects, the prints represent a vision that, in numerical terms alone, impresses by the scope of its ambition. To survey the series as a whole is to witness the gradual but inexorable unfolding of extended variations on chosen themes. At the same time, each separate image appears as the unique product of that ambition, distilled and concentrated within particular marks and shapes. Individual inspection of the works reveals a sustained engagement with a restricted range of motifs in which the resulting images are distinguished by a remarkable diversity. Yet Virtue's treatment of two markedly different topographical subjects has a surprising unity. It is as if, collectively, the monotypes proceeded from some deeper, hidden, single source from which his work, in its entirety, derives. As such, while the monotypes mark a new departure for Virtue, they also extend preoccupations present from the outset.

Since 1978, when his first mature works were made, the central subject of Virtue's art has been the experience of landscape. Taking the places where he has lived and worked as his starting point, walking and drawing in situ have been fundamental, providing a method and a way forward. From 1978 to 1988, his home was Green Haworth, an isolated and austere Lancashire village which he committed to paper in hundreds of small, intensely worked drawings in ink. From 1980, he arranged these images in large mosaic-like formations which he went on to overlay with passages of paint. In so doing, he breached the issue of scale. Close up, these tessellated panels read in terms of concentrated detail. From a distance, the eye traverses the surface and registers its expressive energy. Since then, his activity comprises images that are large and physically imposing, and those that are tiny, yet no less resolved. It is a characteristic of Virtue's outlook, and one advanced powerfully by the monotypes, that his work is undifferentiated, in expressive terms, by issues of scale. The monotypes move seamlessly between expansive panoramas and diminutive evocations of space. But here, as ever, small images are never condensed versions of larger works. Whatever its physical dimensions, each work exists on its own terms as a complete, unqualified statement - indeed, as a defiant fact.

Between 1988 and 1997, Virtue lived in South Tawton in Devon. As would be the case in each of his moves to a new location, his way of working adapted with astonishing freedom to the demands exercised by the character of his surroundings. Overlaid with paint, the tessellated landscapes made in Gleen Howarth had moved increasingly towards greater expressive depth. In Devon, he extended this broader, more gestural approach. Using unstretched canvas laid directly on the ground, Virtue now made paintings in the landscape itself, responding directly to the observed subject. If previously his work had shattered the implications of scale, now he dissolved the distinction between drawing and painting, the unstretched canvas forming a sheet that received a spontaneously improvised drawing in paint. From this point, there is the compelling evidence of an absolute continuum between drawing and painting. This ethos has directed the course of his art, and it feeds directly into the monotypes where the relationship between these two modes of expression achieves an ideal synthesis.

The method that defines Virtue's present, distinctive way of working originated ten years ago. In 1997, he moved again, this time to Exeter. For the next five years he made the Exe estuary his subject, and in his response to that motif, a characteristic pattern or ritual emerged. At the same time, on the same day every week, Virtue commenced an eleven-mile walk down the estuary. During the course of his journey, he paused at the same spots and made rapid sketches in the eight fresh sketchbooks he carried with him. All the time, his walk proceeded towards a distant destination: the tower of All Saints Church, just visible on the horizon. By the end of the day, he would have filled each of the books with drawings, some four hundred images in all. Back in the studio, those quickly executed sketches formed an ever-growing library of visual references: thousands of drawings, a diary of observation and endurance, which fed the formation of paintings. In the isolation of his workplace, Virtue used the drawings to re-enact and re-invent his earlier experiences in the landscape, exploring his imaginative engagement with an external subject in the form of paintings executed in acrylic, ink and shellac on stretched canvas. Once again, there was the evidence of a will to dissolve boundaries. Virtue's sensibility now increasingly straddled direct observation and imaginative invention. This characteristic, too, is central to the way the monotypes were made, demonstrating that Virtue’s work continues to sustain a tension between these opposing forces.

Virtue’s paintings of the Exe valley have an ostensible rural subject, and these works marked the emergence of sky and water as dominant elements in his imagery. Typically, the landscape is suspended between vast looming space filled with movement and, below that, its reflected presence in the form of fugitive shapes on a shifting surface. At the centre of this visual drama, the church tower forms a focal point, nailing an image that seems on the verge of disintegration. This device - a still centre amidst chaotic forces - endures to the present. In the monotypes of London and Venice, the domes of St Paul's and Santa Maria Della Salute have a similar presence and function, traceable to earlier appearances of a church tower in the Exe paintings and, before that, in the Green Howarth drawings.

When Virtue left Exeter for London in 2002, he exchanged a rural subject for one rooted in the architecture and energy of the metropolis. As associate artist at the National Gallery, Virtue occupied a large studio beneath the historic building on the edge of Trafalgar Square. Latterly, his workplace was a confined arched space beneath Waterloo Bridge, near the Courtauld Institute. Over the next five years, London became Virtue's sole subject and, as with his earlier relationships with his surroundings, something of an obsession. Working in close proximity to the Thames, his daily routine involved walking to the jetty on the river's south bank or sometimes descending onto the mud below. From these positions he made innumerable drawings of the view looking towards Blackfriars Bridge and the City. Back in the studio, these intensely wrought fragments were the source material for paintings, forming an ever-growing lexicon of shapes and marks from which the original experience of standing by the river's edge could be explored afresh. The London paintings are a world away from their predecessors which were set in nature. A new formal language emerged, one dominated by architectural shapes. Domes, bridges and jetties formed a new skyline, unmistakably man-made. Yet the sky and the land, light and water, air and reflection are common to both Virtue's rural and urban subjects and provide an essential link between them. Indeed, it is apparent that for Virtue, the relationship of these elements has a deeper, ontological significance that transcends locale. In the paintings both of the Exe estuary and of London and now in the monotypes of London and Venice, the skyline is an idée fix: a vital track of visceral energy coursing through an uncertain space.

The original idea for Virtue's monotypes came in the form of an invitation from Marlborough Gallery, made in August 2006 that he participate in a scheme run in cooperation with the International School of Graphics in Venice. Now in its sixth year, the scheme provides artists with the opportunity of spending three weeks in Venice making prints. Virtue viewed this prospect with some trepidation. His way of working presumes a close, prolonged visual involvement with his immediate surroundings so that he is, in a sense, steeped in his subject. Venice would be a new motif, and as his time there would be limited, the proposed project would entail his articulating an almost immediate response compressed into a relatively short period. His usual process involved extended familiarisation with his surroundings, walking, looking, drawing and - during painting - the prolonged reworking of particular images. It appeared that all this would be completely negated.

He also foresaw a further, fundamental difficulty. Virtue was completely unused to the process of making monotypes. Indeed, with the exception of some earlier etchings, printing was an entirely unfamiliar medium, all his work having been concentrated on painting. As a way of making images, printmaking seemed alarmingly unsympathetic and unsuited to an ethos rooted in isolation and founded on the directness of drawing on paper and painting on canvas. Making prints would involve skilled intermediaries. There would also be an inevitable hiatus between the formation of an image on the printing plate and its transfer to the sheet of paper receiving that image. As a result, he had no confidence whatsoever that working in this way, he could make prints at all. Despite these misgivings, Virtue decided to try.

In October 2006, he was introduced to the printers Mike Taylor and Simon Marsh, both of Paupers Press. For the last five years, Taylor and Marsh had been running the Venice summer workshops, working with other invited artists, and they were to be involved with producing the prints. In order to familiarise himself with the monotype technique, Virtue began making images of the Thames subject on metal printing plates, working from his usual vantage point on the river’s south bank. In this way, he addressed a motif with which he was already closely involved and preparing the prints in front of the motif would, he felt, be no different from his regular drawing ritual. This opening gambit was something of a disaster. Virtue hated working on the spot encumbered with printing plates and found he was unable to proceed in this way. The breakthrough came when he realised that he could simply adapt his existing practice. Reverting to making drawings on paper in the landscape, he then used these studies as a basis for the prints, the plates for which were prepared at Paupers Press. When he came to create the monotypes in the studio, he found that he could work in ways that closely resembled his painting technique. Using the drawings for reference, the images he improvised on the printing plates came quickly, brushes, rags, and sprays being employed to keep the motif in movement. As before, another boundary had been dissolved as drawing, painting and printing were now brought into alignment. Central to Virtue’s monotypes is that they are effectively paintings on paper, and as such, they are a continuation of his work as a painter.

Between October 2006 and March 2007, Virtue translated the Thames subject into a monotype, a medium that became increasingly attuned to his needs. By the end of this period, he had made 129 prints in various sizes. This is a prodigious output, given his previous unfamiliarity with this way of working. One of the most remarkable characteristics of these prints - in addition to their closeness to his paintings of this subject - is the sustained intensity common to both ways of working. It is clear that from the outset, Virtue was determined to make no concessions to the change of medium or method. As in the works on canvas, the monotypes are dominated by the ever-present dome of St Paul's cathedral. Virtue's extended treatment of this motif wrests it from simple connotations of architecture. While it forms a recognisable point of reference and anchors the expressive energy within each image, Virtue's response transcends the topographical. Wren's masterpiece undergoes a relentless process of interrogation and transformation. In London No 127, its bulbous profile is seen from afar, part of a longer, sinuous skyline. In London No 47, it is ascendant, drawing the eye to the centre of the image. At times, it is a brooding shape, black and ominous. In London No 26, it is an ethereal presence, suffused with light, on the point of disappearing. Virtue's response is that of one protagonist to another. His depiction of St Paul's invests the motif with qualities of changing character and mood: human qualities that impart a sense of life.

In terms of their facture, the London monotypes represent the seamless transition of an existing and ongoing subject from the medium of paint to that of monotype. There is the familiar evidence of rapidly brushed marks, spraying, wiping back and the progressive re-working of the image. That said, the monotypes are not simply analogues for the paintings. They also significantly extended Virtue's way of working. Whereas the surfaces of the paintings frequently attest a process of protracted change, the prints retain a feeling of spontaneity. Japanese brush painting is a long-standing model for Virtue's practice and is a digested element of his approach to markmaking in his paintings. The fluidity of the print medium meant that the monotypes could be made with greater speed, and the image could be manipulated more easily. Entire passages could be wiped away and supplanted with swiftly made marks. No less substantial than the paintings in terms of their content, the London monotypes nevertheless move towards a more abbreviated form of expression.

Making the monotypes in London formed a vital preparation for Virtue's impending work in Venice. His initiation stretched over six months and came to a halt in March 2007. A gap of over four months ensued, during which he continued to paint and, coincidentally, oversaw the final stages of a long-contemplated move to Italy. During this time, some of the lessons he had learnt from making monotypes began to filter through to the paintings on which he was then engaged so that the two ways of working cross-fertilised. Following this break with printing, he then took up his pre-arranged appointment and arrived in Venice on 13 August 2007. He immediately confronted a startling new subject: a place he had visited only once previously, yet one he felt he knew through his long-standing acquaintance with Turner's great watercolours of a city dissolved by light. Venices's miraculous marriage of architecture, sky and reflection presented a view at once entirely alien yet also immediately familiar, even ingrained. Yet, as he had anticipated, the prospect of engaging with a subject so steeped in history and, it has to be said, so patinated by the accretion of cliché was utterly intimidating.

The Venice monotypes can be seen as the outcome of a remarkable concentration of Virtue's usual practice. His first imperative was to seek out the motifs on which he would focus. Among the options he considered were the bridge at the Rialto and the square at San Marco. Neither gelled as subjects, and he rejected both. Using waterbuses to get around the city, his attention then focused on the lagoon itself, and finally, two subjects seemed to strike a chord. The motifs that form the basis for Virtue's entire output are those of the domed basilica of Santa Maria Della Salute and the island of San Giorgio Maggiore.

Virtue’s time in Venice fell into two phases: the first week was spent drawing in situ, the final fortnight was taken up by an intensely focused and ultimately exhausting, round-the-clock confinement in the printmaking studio. Notwithstanding his earlier involvement with the London monotypes, he began in a state of complete uncertainty. Virtue was concerned by the way that the transfer of the impression during printing would inevitably reverse the image. He experimented by making the initial drawings on tracing paper, thinking that the sheet could be simply turned over to provide a reversed visual reference when working on the printing plate. This approach proved too cumbersome and was abandoned as if realising that the images he would make had to be liberated from literal description. An extraordinary aspect of the Venice monotypes is that while the images do reverse, the appearance of the subject is virtually imperceptible, so completely are they imbued with the essence of the place.

The will to penetrate the character of a motif and then withdraw, standing at an abstracted remove from the source and reinventing it under the pressure of subjective forces, is central to Virtue’s work. This imperative dominates the Venice monotypes. For this reason, it is not surprising that during the initial experimental phase, Virtue resisted the suggestion that the monotypes employ colour. Since 1978, his art has been restricted to black, white and a spectrum of intermediate greys. His use of monochrome is, in some ways, one of his work's most conspicuous characteristics and has an almost ethical force. There is a sense he believes that colour would qualify or embellish the material fact- and clarity- of his vision. In Venice, the formation of the images proceeded from observation and its opposite: invention. This dichotomy demonstrates his awareness that we do not see the world directly but apprehend it through the lens of experience, through the subjective structures we impose upon external reality. The expressive, gestural force of Virtue's imagery is a powerful vehicle for that vision. His images evince a struggle to make visible what he describes as ‘actuality', a view of the world in which the objective and the subjective are held in balance. Colour would add to the difficulty of stating that actuality as directly as possible. With notable exceptions, the monotypes he went on to make are, like his paintings, rooted in a monochrome language of form and feeling.

Having set his compass with these decisions, the monotypes represent the growing freedom he felt to manipulate time, space, architecture, light and water. It is perhaps a paradox that the Venice images, in common with his wider practice, entailed this close involvement with place and, at the same time, they reflect an impulse wilfully to disrupt topography, history and description. By these means, Virtue engaged with subjects endlessly reproduced both on the pages of art history books and as postcards for the tourist trade. And yet, against these odds, he succeeds in refracting these familiar motifs in unexpected ways so that they resonate with new connotations of feeling and meaning.

Working in the studio during the final two weeks, Virtue called upon the drawings he had made: a huge repository of visual information. These studies traversed the motifs by presenting them from multiple different views. As he improvised around this material in new images made on the printing plates, the two motifs yielded an astonishing richness of variation, complex development and recapitulation. Progressively, the source material was extended and transformed, each print adding continuously to an expanding diversity of treatment in terms of handling, scale, format and markmaking. The pattern that emerged was one of increasing freedom, economy and invention. Prints completed earlier in proceedings are close to the initial subject. They are remarkable evocations of light and reflection, atmosphere and space. From the start, Virtue embraced a variety of shapes and different scales, so many images are presented as tondos or ovals. These formats occasionally invest the images with the character of a view seen through the lens of a camera obscura - at once immediate yet removed from direct visual contact. The abstractedness of the images deepened as Virtue gained increasing confidence, and there is an expressive vitality that subsumes description. By the end of the series, Virtue achieves an ambiguous spectral quality. Individually and collectively, the prints impart a unique experience: the sight of Venice caught up in its own mystery, enveloped by the means of its representation.

By 31 August, the date which signalled the end of the project, Virtue had completed over three hundred prints, of which sixty were destroyed as part of an ongoing editing process. The implications of this astonishing achievement can be sensed: over a two-week period, his output had continued without abatement and, in fact, only finally ended when the stock of paper was exhausted. On his return to London, there was a remarkable coda when, in midSeptember, he completed a further four large-scale Venice prints: magisterial images in which the entire experience received a complex and fully developed summation. Shortly afterwards, Virtue closed down his painting studio and left London to live in Italy. In so doing, he vacated the city that had provided his subject for the previous five years to continue his work in a new location. In telling ways, the London and Venice monotypes stand at this important juncture in Virtue’s art. They draw together themes that have governed the progress of his work for almost thirty years, and they point the way to its future development.

-

-